One-line summary: This satirical story about a Bible-thumping charlatan still annoys evangelical Christians, because it's still spot-on.

First published by Harcourt, Brace, in 1927; 432 pages

Thanks to this best-selling novel and the 1960 film, Elmer Gantry is synonymous today with the sort of evangelical huckster who's familiar to Americans (and the world), but when Sinclair Lewis wrote it in 1927, it shocked the country with its cynical depiction of American religion. Unsurprisingly, the book and the author were not very popular with the clergy or evangelical Christians.

The first thing to understand about this book is that it is steeped in American Protestantism, which is of a peculiar and unique flavor (though it's now been exported worldwide). If you've grown up in that culture, even if you're not a Protestant church-goer yourself, then you'll recognize the people Sinclair Lewis is writing about. If you're not an American, have never done time in Sunday School or sitting in pews, or you don't quite understand why anyone cares about minute differences in the theological soup of Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians, Lutherans, Episcopalians, Assemblies of God, Church of Christ, et al, then some of the nuances of the story may seem silly and irrelevant (and some of the incidents unbelievable), but you'll certainly get a sense of the flavor of the times, a culture that still pervades America to this day. It is set in the time period circa 1901 to about 1930, but the small town churches where most of the action takes place haven't changed much. (There may not be quite so many preachers nowadays railing against the moral hazards of dancing and reading novels, but the anti-evolution screeds and the frothing about liberals and atheists hasn't changed at all.)

Not all the Christians in this novel are bad people; most are just ordinary people. But Lewis mercilessly skewers the hypocrites and the merchants in the temple, of whom Elmer Gantry is only the most outrageous example.

Elmer Gantry is a college athlete whose primary interests are drinking and womanizing. Thoroughly irreverent despite attending a religious university, Gantry is a big, bullying fellow who's reasonably intelligent and not completely bad, but he's not very nice, nor is he given to much reflection. Lewis's depiction of Elmer and his immersion in the evangelical world is the strongest aspect of the book. In particular, Elmer Gantry is a perfect study of hypocrisy and rationalization in action. Although Elmer is not a very nice person (and he only becomes worse as he grows in power and influence), he's not a sociopath, which means occasionally he has pangs of guilt. He doesn't like to think of himself as a bad person, even though he almost never does anything that's not completely self-interested. So we get to see his mind at work as he lies, cons, defrauds, bullies, extorts, and seduces his way through life, committing every sin he preaches fiery sermons against while convincing himself that he's still a moral man of God. He leaves a trail of ruined lives behind him, yet convinces himself that everything he does is justified. To the outside observer, Elmer Gantry is obviously a hypocrite and a horrible human being, but Lewis lets us see him as he sees himself, and it's completely convincing.

Somewhat less vivid, but just as convincing, are the minor characters who populate the novel. Gantry is by no means the only hypocrite in the book, though few are as spectacularly, sinfully degenerate as him. The ideal of being "called" to the ministry is juxtaposed with the reality of career clergy who see their profession as a job like any other. There are preachers who are secretly agnostic or outright atheists (a cynical notion that shocked Lewis's readers, but which is in fact not as rare as you might think). There are a lot of women, and a few friends, who pass through Elmer's life.

And then, there is Sharon Falconer.

After Elmer has been kicked out of his Baptist ministry (the first of many sex scandals), he becomes assistant to a woman evangelist who leads a traveling revival outfit. She preaches a fairly bland strain of evangelical Christianity, and ruthlessly wrings money out of the churches and crowds she visits. She's as big a huckster as Gantry, every bit as hypocritical and self-serving -- and at the same time, she's perfectly genuine. She really does believe she's a prophet. She's brilliant and charismatic and a complete phony; she doubts and disparages herself while being filled with a conviction to rival Joan of Arc's. She bewitches Elmer, who loves, envies, and admires her while believing women can't really lead a ministry and she should let him take over.

And she's completely batshit insane. My favorite scene is when she brings him to her "ancestral home" in Virginia (which turns out to be an old estate she bought a few months ago) and leads Gantry (who thinks he's about to finally get himself a piece) into her private chapel:

Despite blowing his mind with the realization of just how bonkers she is, Elmer only becomes more infatuated. His relationship with Sharon Falconer was actually one of the most touching parts of the book. She haunts him for the rest of his life, and while he eventually marries (and treats his wife horribly), it's Sharon he always misses. In fact, though he indulges in every other sin and vice, he quits smoking and drinking at Sharon's behest, and sticks to that promise long after she is gone.

After his stint with Sharon Falconer, Elmer spends a little time as a New Thought charlatan (this time he even admits to himself that he's spouting bullshit), and then, with the same cheerful opportunism that has marked his career, cons his way into the pulpit again as a Methodist minister. He spends the rest of his life as a Methodist, his power and influence spreading as he moves on to bigger and bigger churches.

(Incidentally, this is one of the things that has changed since Sinclair Lewis's day; the Methodists used to be among the more hard-line Protestant denominations. Fundamentalist Methodist congregations certainly still exist, but the Methodist church today is generally one of the more liberal denominations.)

As a historical novel, Elmer Gantry shares much in common with the novels of Lewis's similarly-named contemporary Upton Sinclair as a satirical critique of American Protestantism. As a story, it's the biography of a fictional huckster who might seem too over-the-top to be credible, except that you can turn on the TV and see far more over-the-top hucksters preaching today. Elmer Gantry is set before the days of radio and television evangelism, but Sinclair Lewis certainly saw them and mega-churches coming. As for characterization, the main character is a louse and you're not meant to like him, but I've never read a more compelling and spot-on portrayal of hypocritical delusion and cognitive dissonance.

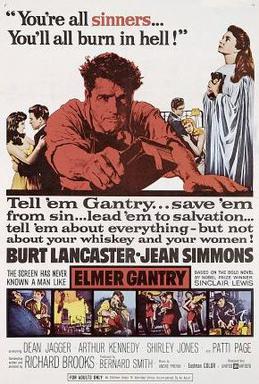

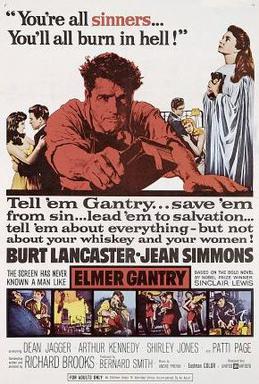

This 1960 movie won three Oscars, but it didn't have nearly the guts of the novel. Hollywood was still terrified of offending churches, which is why the movie starts by rolling an apologetic marquee warning that this "very controversial" film shouldn't be shown to children.

It's not a very faithful adaptation; despite being over two hours long, it only covers Elmer Gantry's time with Sharon Falconer, which was maybe a third of the book. Everything that made Gantry what he was, and his subsequent career, were omitted. Burt Lancaster's Gantry was also a much more sympathetic character; while he's still a boozing, womanizing huckster, he's not nearly the self-serving hypocrite he was in the book, and he shows a gallantry and even a degree of faith that was absent in Lewis's character. Unsurprisingly, Sharon Falconer is also pure Hollywood supporting actress, and there are no crocodile-headed gods or prayers to Frigga and Astarte. Still, for 1960 this was probably a pretty radical film, and if you watch it as a movie in its own right and not as an adaption of a book, it's dramatic and well-acted.

(Also, amusingly, one of the small details the movie did borrow from the book was the author's name-checking himself with a sneering reference to "those atheists like Sinclair Lewis.")

Verdict: Books written generations ago about a time period even further back may or may not seem relevant today. Sinclair Lewis was enough of a writer for his books to still be readable and his characters contemporary. Elmer Gantry is a bit dated, but it remains entertaining and smart, and probably a lot more enjoyable if you don't mind seeing religion poked with a sharp stick.

First published by Harcourt, Brace, in 1927; 432 pages

Today universally recognized as a landmark in American literature, Elmer Gantry scandalized readers when it was first published, causing Sinclair Lewis to be "invited" to a jail cell in New Hampshire and to his own lynching in Virginia. His portrait of a golden-tongued evangelist who rises to power within his church - a saver of souls who lives a life of hypocrisy, sensuality, and ruthless self-indulgence - is also the record of a period, a reign of grotesque vulgarity, which but for Lewis would have left no record of itself. Elmer Gantry has been called the greatest, most vital, and most penetrating study of hypocrisy that has been written since Voltaire.

Thanks to this best-selling novel and the 1960 film, Elmer Gantry is synonymous today with the sort of evangelical huckster who's familiar to Americans (and the world), but when Sinclair Lewis wrote it in 1927, it shocked the country with its cynical depiction of American religion. Unsurprisingly, the book and the author were not very popular with the clergy or evangelical Christians.

The first thing to understand about this book is that it is steeped in American Protestantism, which is of a peculiar and unique flavor (though it's now been exported worldwide). If you've grown up in that culture, even if you're not a Protestant church-goer yourself, then you'll recognize the people Sinclair Lewis is writing about. If you're not an American, have never done time in Sunday School or sitting in pews, or you don't quite understand why anyone cares about minute differences in the theological soup of Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians, Lutherans, Episcopalians, Assemblies of God, Church of Christ, et al, then some of the nuances of the story may seem silly and irrelevant (and some of the incidents unbelievable), but you'll certainly get a sense of the flavor of the times, a culture that still pervades America to this day. It is set in the time period circa 1901 to about 1930, but the small town churches where most of the action takes place haven't changed much. (There may not be quite so many preachers nowadays railing against the moral hazards of dancing and reading novels, but the anti-evolution screeds and the frothing about liberals and atheists hasn't changed at all.)

Not all the Christians in this novel are bad people; most are just ordinary people. But Lewis mercilessly skewers the hypocrites and the merchants in the temple, of whom Elmer Gantry is only the most outrageous example.

Elmer Gantry is a college athlete whose primary interests are drinking and womanizing. Thoroughly irreverent despite attending a religious university, Gantry is a big, bullying fellow who's reasonably intelligent and not completely bad, but he's not very nice, nor is he given to much reflection. Lewis's depiction of Elmer and his immersion in the evangelical world is the strongest aspect of the book. In particular, Elmer Gantry is a perfect study of hypocrisy and rationalization in action. Although Elmer is not a very nice person (and he only becomes worse as he grows in power and influence), he's not a sociopath, which means occasionally he has pangs of guilt. He doesn't like to think of himself as a bad person, even though he almost never does anything that's not completely self-interested. So we get to see his mind at work as he lies, cons, defrauds, bullies, extorts, and seduces his way through life, committing every sin he preaches fiery sermons against while convincing himself that he's still a moral man of God. He leaves a trail of ruined lives behind him, yet convinces himself that everything he does is justified. To the outside observer, Elmer Gantry is obviously a hypocrite and a horrible human being, but Lewis lets us see him as he sees himself, and it's completely convincing.

Somewhat less vivid, but just as convincing, are the minor characters who populate the novel. Gantry is by no means the only hypocrite in the book, though few are as spectacularly, sinfully degenerate as him. The ideal of being "called" to the ministry is juxtaposed with the reality of career clergy who see their profession as a job like any other. There are preachers who are secretly agnostic or outright atheists (a cynical notion that shocked Lewis's readers, but which is in fact not as rare as you might think). There are a lot of women, and a few friends, who pass through Elmer's life.

And then, there is Sharon Falconer.

After Elmer has been kicked out of his Baptist ministry (the first of many sex scandals), he becomes assistant to a woman evangelist who leads a traveling revival outfit. She preaches a fairly bland strain of evangelical Christianity, and ruthlessly wrings money out of the churches and crowds she visits. She's as big a huckster as Gantry, every bit as hypocritical and self-serving -- and at the same time, she's perfectly genuine. She really does believe she's a prophet. She's brilliant and charismatic and a complete phony; she doubts and disparages herself while being filled with a conviction to rival Joan of Arc's. She bewitches Elmer, who loves, envies, and admires her while believing women can't really lead a ministry and she should let him take over.

And she's completely batshit insane. My favorite scene is when she brings him to her "ancestral home" in Virginia (which turns out to be an old estate she bought a few months ago) and leads Gantry (who thinks he's about to finally get himself a piece) into her private chapel:

Above the altar hung an immense crucifix with the Christ bleeding at nail-wounds and pierced side; and on the upper stage were plaster busts of the Virgin, St. Theresa, St. Catherine, a garish Sacred Heart, a dolorous simulacrum of the dying St. Stephen. But crowded on the lower stage was a crazy rout of what Elmer called "heathen idols": ape-headed gods, crocodile-headed gods, a god with three heads and a god with six arms, a jade-and-ivory Buddha, an alabaster naked Venus, and in the center of them all a beautiful, hideous, intimidating and alluring statuette of a silver goddess with a triple crown and a face as thin and long and passionate as that of Sharon Falconer. Before the altar was a long, velvet cushion, very thick and soft. Here Sharon suddenly knelt, waving him to his knees, as she cried:

"It is the hour! Blessed Virgin, Mother Hera, Mother Frigga, Mother Ishtar, Mother Isis, dread Mother Astarte of the weaving arms, it is thy priestess, it is she who after the blind centuries and the groping years shall make it known to the world that ye are one, and that in me ye are all revealed, and that in this revelation shall come peace and wisdom universal, the secret of the spheres and the pit of understanding...."

Despite blowing his mind with the realization of just how bonkers she is, Elmer only becomes more infatuated. His relationship with Sharon Falconer was actually one of the most touching parts of the book. She haunts him for the rest of his life, and while he eventually marries (and treats his wife horribly), it's Sharon he always misses. In fact, though he indulges in every other sin and vice, he quits smoking and drinking at Sharon's behest, and sticks to that promise long after she is gone.

After his stint with Sharon Falconer, Elmer spends a little time as a New Thought charlatan (this time he even admits to himself that he's spouting bullshit), and then, with the same cheerful opportunism that has marked his career, cons his way into the pulpit again as a Methodist minister. He spends the rest of his life as a Methodist, his power and influence spreading as he moves on to bigger and bigger churches.

(Incidentally, this is one of the things that has changed since Sinclair Lewis's day; the Methodists used to be among the more hard-line Protestant denominations. Fundamentalist Methodist congregations certainly still exist, but the Methodist church today is generally one of the more liberal denominations.)

As a historical novel, Elmer Gantry shares much in common with the novels of Lewis's similarly-named contemporary Upton Sinclair as a satirical critique of American Protestantism. As a story, it's the biography of a fictional huckster who might seem too over-the-top to be credible, except that you can turn on the TV and see far more over-the-top hucksters preaching today. Elmer Gantry is set before the days of radio and television evangelism, but Sinclair Lewis certainly saw them and mega-churches coming. As for characterization, the main character is a louse and you're not meant to like him, but I've never read a more compelling and spot-on portrayal of hypocritical delusion and cognitive dissonance.

Of course there was a movie, too

This 1960 movie won three Oscars, but it didn't have nearly the guts of the novel. Hollywood was still terrified of offending churches, which is why the movie starts by rolling an apologetic marquee warning that this "very controversial" film shouldn't be shown to children.

It's not a very faithful adaptation; despite being over two hours long, it only covers Elmer Gantry's time with Sharon Falconer, which was maybe a third of the book. Everything that made Gantry what he was, and his subsequent career, were omitted. Burt Lancaster's Gantry was also a much more sympathetic character; while he's still a boozing, womanizing huckster, he's not nearly the self-serving hypocrite he was in the book, and he shows a gallantry and even a degree of faith that was absent in Lewis's character. Unsurprisingly, Sharon Falconer is also pure Hollywood supporting actress, and there are no crocodile-headed gods or prayers to Frigga and Astarte. Still, for 1960 this was probably a pretty radical film, and if you watch it as a movie in its own right and not as an adaption of a book, it's dramatic and well-acted.

(Also, amusingly, one of the small details the movie did borrow from the book was the author's name-checking himself with a sneering reference to "those atheists like Sinclair Lewis.")

Verdict: Books written generations ago about a time period even further back may or may not seem relevant today. Sinclair Lewis was enough of a writer for his books to still be readable and his characters contemporary. Elmer Gantry is a bit dated, but it remains entertaining and smart, and probably a lot more enjoyable if you don't mind seeing religion poked with a sharp stick.