The bloody and terrible history of the Comanche.

Scribner, 2010, 384 pages

This book is about the Comanche, one of the most powerful and warlike tribes of the American Southwest. It actually covers several separate "stories" over the course of the book. First, there is the history of the Comanche people themselves from their earliest beginnings to their final fate as reservation Indians, plains warriors made to become farmers. There are a lot of chapters about warfare between the Comanche, other Indian tribes, and the Spanish and the Americans, and woven through it, the stories of Cynthia Ann Parker, one of the most famous white women of the Old West who was captured as a child by the Comanche, raised as one of their own, later was "rescued" (actually recaptured) by whites, and lived a miserable life in captivity as the celebrated ex-squaw of a Comanche war chief.

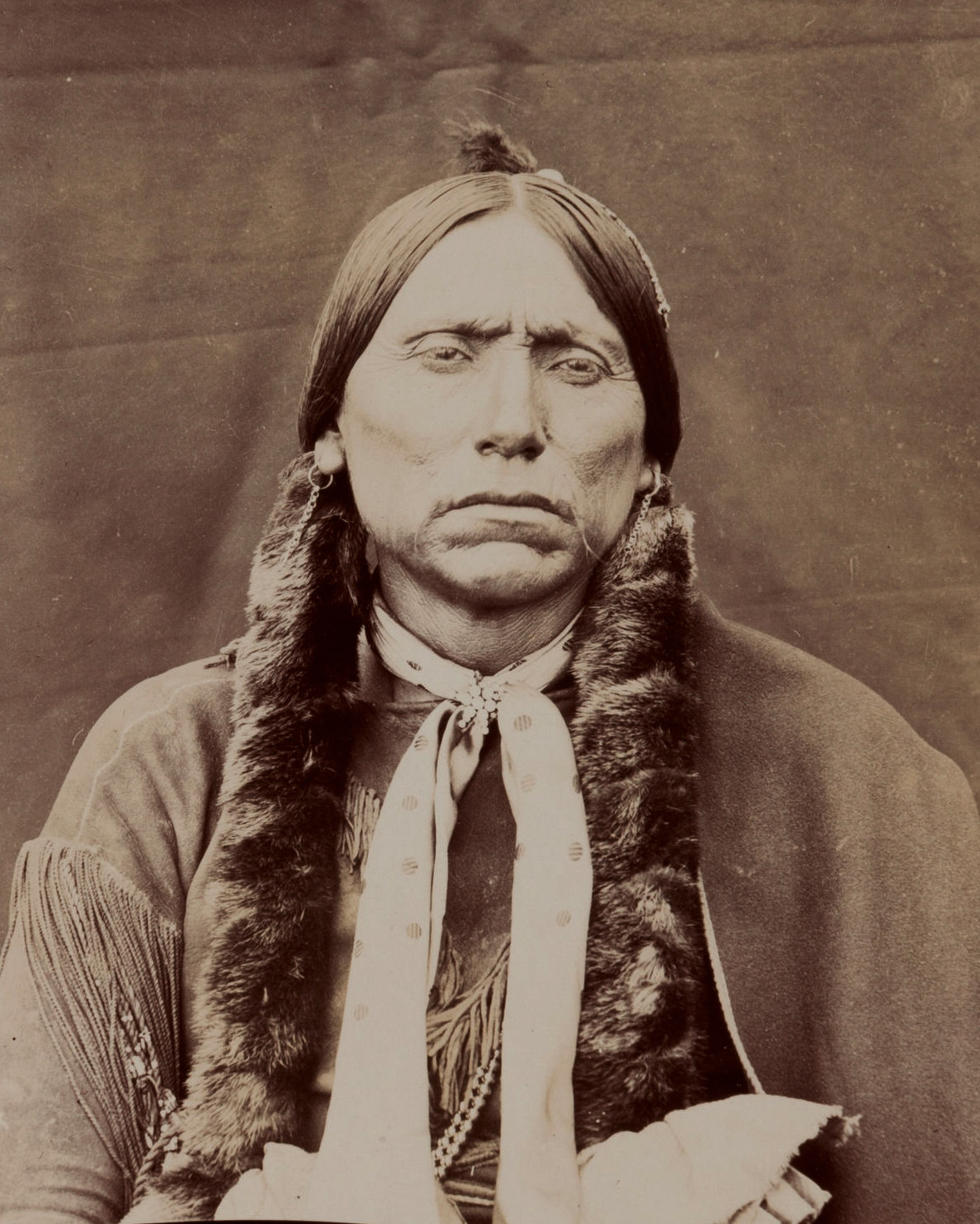

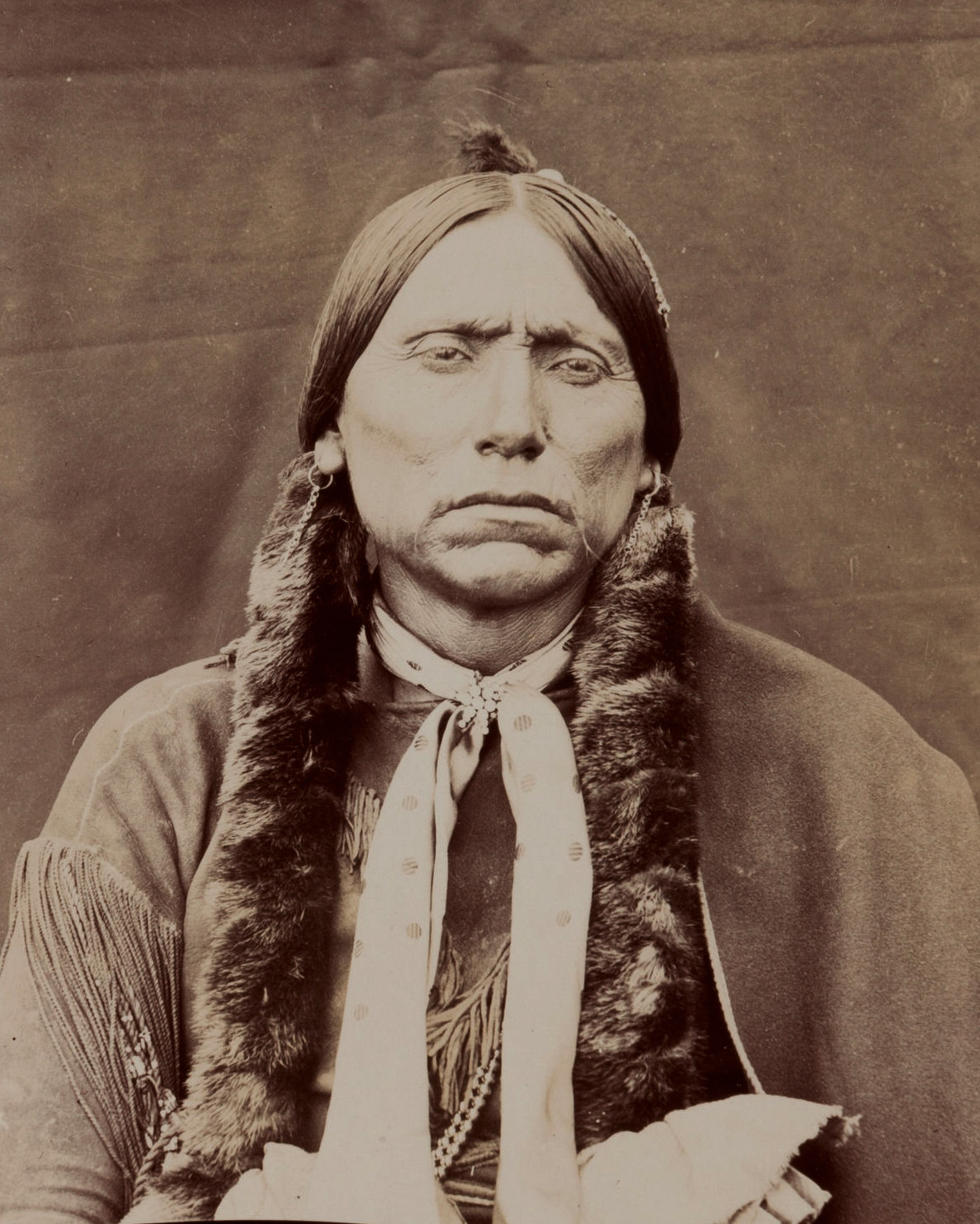

Her son, however, was more famous still - Quanah Parker, last of the Comanche chiefs, first and only "Chief of Chiefs" (in a tribe that had no precedent for such a title), a "reformed" Indian warrior who once murdered and scalped his way across the American Southwest, but later became a politician, a school board member, and as he told a Texas State Fair crowd towards the end of his life, "A taxpayer, just like you."

This book, like Quanah Parker, is full of conflict. Empire of the Summer Moon has been highly praised and rated, and nearly won a Pulitzer. It's a good book, well-written and interesting and full of fascinating, sometimes gruesome, stories.

But it's also been heavily criticized. A lot of Native Americans, unsurprisingly, do not like its depiction of the Comanche. Reviewers have called it "racist, colonialist," etc.

Americans have for generations suffered an enormous collective guilt complex over what we did to the Indians. Nowadays, it is hardly even debatable that Europeans committed atrocities and stole the Indians' land. The fact that this is just the way things were done a few centuries ago, and we're only now, worldwide, shifting to a global society that kinda sorta no longer approves of bigger, more technologically advanced countries invading smaller countries and taking their land and subjugating their populations just because they can, does not seem to mitigate the "original sin" of America's founding. (And that of Canada and basically every other country in the Western hemisphere.)

So understandably, when talking about how "savage," "primitive," and "bloodthirsty" some Indians were, it raises hackles today. Those are loaded terms, and S.C. Gwynne uses them a lot. He repeatedly refers to the Comanche as "stone-aged" and observes that they had "no sense of history," "lacked the elaborate social structure of other tribes," and generally describes them as, well, a warlike tribe of rapacious stone-aged torture-happy marauders.

Gwynne certainly describes the atrocities and corruption for which Texas and the United States were responsible. (For much of the book, the two are not synonymous, and the Comanche in particular drew a distinction between the hated "Texans" and everyone else.) Despite what some people have written, this is not a Comanche-bashing book or one that says White Man Good, Indian Bad.

The problem is, the things Gwynne says are objectively true. The Comanche were a stone-aged civilization. They eventually acquired horses, which they mastered as few other people have in history, and firearms, which they could not repair or maintain. They had almost no technology or art or culture of their own, or any sort of social structure above the level of tribes, which were run in very straightforward "alpha dog" style.

To be honest, it's hard for me to escape judging the Comanche as pretty terrible people.

I don't mean that every single Comanche was evil, or that whatever their faults as a society, that justified white people exterminating them and taking their land. But the Comanche, like most of the plains tribes, were vicious and cruel. They fought wars of extermination, had no concept of mercy, and captives were routinely gang-raped and tortured to death. As Gwynne points out, this set them apart from Eastern Indians, who also frequently practiced torture, but not so much rape.

Plains warfare was brutal and merciless. But if you believe there is such a thing as objective right and wrong, if you have any qualms at all about cultural relativism, then you have to have qualms about a civilization in which it is a social norm to rape and torture to death anyone who's not of your tribe.

And make no mistake, the Comanche and their neighbors were doing this long before Europeans came to the New World, it's not something they were taught by the White Man. The "Noble Savage" myth, which Gwynne describes being very much alive during the 19th century, often hindered how the United States dealt with the Comanche because many Americans, including members of Congress, genuinely believed that the Indians were only warlike and vicious in response to white provocations, and that if they were dealt with fairly and peacefully, they would also be peaceful, good neighbors.

The Comanche's entire history said otherwise. They were never going to settle down and stop raiding and raping and torturing until forced to.

How exactly we should have gone about this, and why we were in that position, are legitimate questions. And certainly once the pattern started, of Comanches committing atrocities upon whites (just as they had upon the Mexicans, and the Apaches and the Kiowa and the Navajo and everyone else they ever encountered), whites committed atrocities right back. One can kind of understand how Texans faced with Comanche aggression came to believe that "the only good Indian is a dead Indian," even while being appalled at the sentiment. There weren't really any "good guys" but there also weren't any clear-cut "bad guys." If you believe whites were the bad guys for being on the Indians' land - well, maybe, but population migrations happen, and the Indians certainly moved about and exterminated other tribes and took their land, long before it was done to them by non-Indians.

It's easy to see how this book raises conflicting feelings and some strong reactions. One of the criticisms I will say is more valid is that Gwynne only seemed to consult historical records by Americans and other Europeans. There are still Comanche alive today. I would have liked to have heard their own version of their tribe's history, and I may search out other available sources. I don't know if modern Comanche dispute the early settlers' accounts of their ancestors' savagery, or if they claim it was justified in response to white encroachment on their land, or if they also accept that this was the way things were back then, and that it's better that that way of life is gone.

All of that being said, Empire of the Summer Moon was very educational, and you'll surely learn a lot whether or not you agree with the author's viewpoint. (To be clear, most of what I say above is my viewpoint - the author tries to stay more or less objective, though at times it's hard to be non-judgmental about the extremely gruesome and sadistic way in which the Comanche treated captives.) The Comanche, "primitive" or not, were not stupid. They practiced brilliant strategy and could be brave, sneaky, and adaptable as the situation required. They started as true primitives, but like most plains tribes, it was the arrival of the horse, first brought by the Spanish, that transformed them. The horse was not a native to North America, but by the time the Texans and Americans had to contend with the Comanche, the Comanche had been horseback riders for hundreds of years and it was in their blood.

We often assume today that battles between soldiers and Indians were always one-sided affairs except when, as at Little Big Horn, the Indians had overwhelming superiority in numbers. But in fact, early on the Indians were far superior militarily to the Europeans and Americans. While guns certainly gave the white man an advantage (Indians would buy, trade, or steal for firearms, but could never produce or maintain them), early firearms were no match for Comanche bows, that were deadly out to 20 or 30 yards and could be fired many times faster than the single-shot muskets and carbines of the bluecoats. Also, at first the Texans practiced European warfare tactics - dismount to face a charging enemy with your guns. Against mounted cavalry like the Comanche, this was suicide.

The Comanche had a vast "empire" and rightly perceived Texas as encroaching upon it. So when the two civilizations met, it was inevitable that there would be bloody warfare, and at first, whites were unprepared for just how numerous and powerful the Comanche were. For a time the Comanche actually turned back westward expansion and rolled back the frontier.

Several more times in the 19th century, before the Comanche were pacified for good, they would break out of their reservations and quietude and go on a rampage that would practically shut down all commerce and throw the entire West into a panic.

The Comanche led to the formation of the Texas Rangers - a small force whose size and exploits may have been exaggerated, but which nonetheless was the first truly effective Indian-fighting force in the West. They learned to hunt, track, and fight Indian style, and when supplied with what was at first an obscure new invention that no one else wanted - the Colt 6-shooter - they suddenly had weapons that could truly let them fight the Comanche on their terms.

The history of Indian fighting is interesting wherever you stand on the Cowboys & Indians division, because it's a true military history. The Comanche weren't just war-whooping savages attacking like orcs, they used strategy and tactics and intelligence (they knew when Army units were diverted elsewhere, such as for the Civil War), and they picked their battles. Though they also made frequent mistakes, usually more diplomatic than military. For example, they considered taking white women captive, raping and torturing them, and then ransoming them back to be just normal business practice, and probably never really understood just how implacably this set white men against them.

I did have a bit of a problem with the titular premise of the book - that the Comanche ruled an "empire," akin perhaps to the Mayans or the Aztecs. In fact, as Gwynne points out, the Comanche were divided into five or six large "bands" who considered themselves all one people, but were led by different chiefs, none of whom had authority over the others, and there was no grand council coordinating all Comanche (at least not until the Quanah Parker era, and then only nominally). This was a mistake whites frequently made - they would negotiate a peace treaty with one particular band of Comanches, and think they had signed a treaty with the entire Comanche tribe, when in fact all the other Comanche neither knew nor cared about any agreements with some other band.

And the Comanche were also unlike the Navajo or most of the other well-known large tribes; according to Gwynne, they had little in the way of art, culture, history, or formal tribal structure. They really were quite "primitive," even compared to other Indians. So to speak of a Comanche "empire" seems to be a bit of an exaggeration - what the Comanche actually had was a very large territory over which they hunted and raided and were the acknowledged lords of the plains, until the white man came along.

The latter part of the book is mostly about Quanah Parker. Quanah, the half-white, half-Comanche son of Cynthia Ann Parker (from whom he was separated at age 12, never to see her again), was a truly remarkable individual. Described as a giant among Comanche and unusually strong and intelligent, he suffered some prejudice for his white blood but proved himself over and over again to be a better Comanche than any of his detractors. (The Comanche also were not particularly racial purists - it had long been their practice to capture children from other tribes, and the Mexicans, and then the whites, to raise as their own, supposedly in part because Comanche women, spending long, hard years on horseback themselves, had a very low fertility rate.) He become a notorious war leader, and hated his mother's people, the Texans, in particular.

This is another one of those great contradictions we are confronted with. Quanah Parker, later in life, became feted and celebrated as a "civilized" Indian. He adapted to his life as a homeowner and a celebrity and a politician, was fascinated by new technology, owning a telephone and an automobile. He was friends with Teddy Roosevelt.

But this same man had once ridden the plains and raided white settlements. There is no documented evidence that Quanah personally raped and tortured anyone, but he was known to harbor a vicious hatred for white settlers, he led Comanche war parties, and this was what Comanche war parties did. So, you can draw your own conclusions. Quanah sensibly refused to go into those sorts of details later in life.

In summary, this was a fascinating, somewhat flawed book. It told me a lot of things about the Comanche, some of which I realize I need to treat with some skepticism until I read some other primary sources. It has at least inspired me to go looking for other books on the same subject from which I might get other perspectives.

I've read good reviews of this book, so perhaps it should be next on my reading list.

And now I need to break open this solitaire game from GMT which has been sitting on my shelf for months now.

My complete list of book reviews.

Scribner, 2010, 384 pages

Empire of the Summer Moon spans two astonishing stories. The first traces the rise and fall of the Comanches, the most powerful Indian tribe in American history. The second entails one of the most remarkable narratives ever to come out of the Old West: the epic saga of the pioneer woman Cynthia Ann Parker and her mixed-blood son, Quanah, who became the last and greatest chief of the Comanches.

Although readers may be more familiar with the names Apache and Sioux, it was in fact the legendary fighting ability of the Comanches that determined just how and when the American West opened up. They were so masterful at war and so skillful with their arrows and lances that they stopped the northern drive of colonial Spain from Mexico and halted the French expansion westward from Louisiana. White settlers arriving in Texas from the Eastern United States were surprised to find the frontier being rolled backward by Comanches incensed by the invasion of their tribal lands. So effective were the Comanches that they forced the creation of the Texas Rangers and account for the advent of the new weapon specifically designed to fight them: the six-gun.

The war with the Comanches lasted four decades, in effect holding up the development of the new American nation. Gwynne's exhilarating account delivers a sweeping narrative that encompasses Spanish colonialism, the Civil War, the destruction of the buffalo herds, and the arrival of the railroads - a historical feast for anyone interested in how the United States came into being.

This book is about the Comanche, one of the most powerful and warlike tribes of the American Southwest. It actually covers several separate "stories" over the course of the book. First, there is the history of the Comanche people themselves from their earliest beginnings to their final fate as reservation Indians, plains warriors made to become farmers. There are a lot of chapters about warfare between the Comanche, other Indian tribes, and the Spanish and the Americans, and woven through it, the stories of Cynthia Ann Parker, one of the most famous white women of the Old West who was captured as a child by the Comanche, raised as one of their own, later was "rescued" (actually recaptured) by whites, and lived a miserable life in captivity as the celebrated ex-squaw of a Comanche war chief.

Her son, however, was more famous still - Quanah Parker, last of the Comanche chiefs, first and only "Chief of Chiefs" (in a tribe that had no precedent for such a title), a "reformed" Indian warrior who once murdered and scalped his way across the American Southwest, but later became a politician, a school board member, and as he told a Texas State Fair crowd towards the end of his life, "A taxpayer, just like you."

This book, like Quanah Parker, is full of conflict. Empire of the Summer Moon has been highly praised and rated, and nearly won a Pulitzer. It's a good book, well-written and interesting and full of fascinating, sometimes gruesome, stories.

But it's also been heavily criticized. A lot of Native Americans, unsurprisingly, do not like its depiction of the Comanche. Reviewers have called it "racist, colonialist," etc.

Americans have for generations suffered an enormous collective guilt complex over what we did to the Indians. Nowadays, it is hardly even debatable that Europeans committed atrocities and stole the Indians' land. The fact that this is just the way things were done a few centuries ago, and we're only now, worldwide, shifting to a global society that kinda sorta no longer approves of bigger, more technologically advanced countries invading smaller countries and taking their land and subjugating their populations just because they can, does not seem to mitigate the "original sin" of America's founding. (And that of Canada and basically every other country in the Western hemisphere.)

So understandably, when talking about how "savage," "primitive," and "bloodthirsty" some Indians were, it raises hackles today. Those are loaded terms, and S.C. Gwynne uses them a lot. He repeatedly refers to the Comanche as "stone-aged" and observes that they had "no sense of history," "lacked the elaborate social structure of other tribes," and generally describes them as, well, a warlike tribe of rapacious stone-aged torture-happy marauders.

Gwynne certainly describes the atrocities and corruption for which Texas and the United States were responsible. (For much of the book, the two are not synonymous, and the Comanche in particular drew a distinction between the hated "Texans" and everyone else.) Despite what some people have written, this is not a Comanche-bashing book or one that says White Man Good, Indian Bad.

The problem is, the things Gwynne says are objectively true. The Comanche were a stone-aged civilization. They eventually acquired horses, which they mastered as few other people have in history, and firearms, which they could not repair or maintain. They had almost no technology or art or culture of their own, or any sort of social structure above the level of tribes, which were run in very straightforward "alpha dog" style.

To be honest, it's hard for me to escape judging the Comanche as pretty terrible people.

I don't mean that every single Comanche was evil, or that whatever their faults as a society, that justified white people exterminating them and taking their land. But the Comanche, like most of the plains tribes, were vicious and cruel. They fought wars of extermination, had no concept of mercy, and captives were routinely gang-raped and tortured to death. As Gwynne points out, this set them apart from Eastern Indians, who also frequently practiced torture, but not so much rape.

Plains warfare was brutal and merciless. But if you believe there is such a thing as objective right and wrong, if you have any qualms at all about cultural relativism, then you have to have qualms about a civilization in which it is a social norm to rape and torture to death anyone who's not of your tribe.

And make no mistake, the Comanche and their neighbors were doing this long before Europeans came to the New World, it's not something they were taught by the White Man. The "Noble Savage" myth, which Gwynne describes being very much alive during the 19th century, often hindered how the United States dealt with the Comanche because many Americans, including members of Congress, genuinely believed that the Indians were only warlike and vicious in response to white provocations, and that if they were dealt with fairly and peacefully, they would also be peaceful, good neighbors.

The Comanche's entire history said otherwise. They were never going to settle down and stop raiding and raping and torturing until forced to.

How exactly we should have gone about this, and why we were in that position, are legitimate questions. And certainly once the pattern started, of Comanches committing atrocities upon whites (just as they had upon the Mexicans, and the Apaches and the Kiowa and the Navajo and everyone else they ever encountered), whites committed atrocities right back. One can kind of understand how Texans faced with Comanche aggression came to believe that "the only good Indian is a dead Indian," even while being appalled at the sentiment. There weren't really any "good guys" but there also weren't any clear-cut "bad guys." If you believe whites were the bad guys for being on the Indians' land - well, maybe, but population migrations happen, and the Indians certainly moved about and exterminated other tribes and took their land, long before it was done to them by non-Indians.

It's easy to see how this book raises conflicting feelings and some strong reactions. One of the criticisms I will say is more valid is that Gwynne only seemed to consult historical records by Americans and other Europeans. There are still Comanche alive today. I would have liked to have heard their own version of their tribe's history, and I may search out other available sources. I don't know if modern Comanche dispute the early settlers' accounts of their ancestors' savagery, or if they claim it was justified in response to white encroachment on their land, or if they also accept that this was the way things were back then, and that it's better that that way of life is gone.

All of that being said, Empire of the Summer Moon was very educational, and you'll surely learn a lot whether or not you agree with the author's viewpoint. (To be clear, most of what I say above is my viewpoint - the author tries to stay more or less objective, though at times it's hard to be non-judgmental about the extremely gruesome and sadistic way in which the Comanche treated captives.) The Comanche, "primitive" or not, were not stupid. They practiced brilliant strategy and could be brave, sneaky, and adaptable as the situation required. They started as true primitives, but like most plains tribes, it was the arrival of the horse, first brought by the Spanish, that transformed them. The horse was not a native to North America, but by the time the Texans and Americans had to contend with the Comanche, the Comanche had been horseback riders for hundreds of years and it was in their blood.

We often assume today that battles between soldiers and Indians were always one-sided affairs except when, as at Little Big Horn, the Indians had overwhelming superiority in numbers. But in fact, early on the Indians were far superior militarily to the Europeans and Americans. While guns certainly gave the white man an advantage (Indians would buy, trade, or steal for firearms, but could never produce or maintain them), early firearms were no match for Comanche bows, that were deadly out to 20 or 30 yards and could be fired many times faster than the single-shot muskets and carbines of the bluecoats. Also, at first the Texans practiced European warfare tactics - dismount to face a charging enemy with your guns. Against mounted cavalry like the Comanche, this was suicide.

The Comanche had a vast "empire" and rightly perceived Texas as encroaching upon it. So when the two civilizations met, it was inevitable that there would be bloody warfare, and at first, whites were unprepared for just how numerous and powerful the Comanche were. For a time the Comanche actually turned back westward expansion and rolled back the frontier.

Several more times in the 19th century, before the Comanche were pacified for good, they would break out of their reservations and quietude and go on a rampage that would practically shut down all commerce and throw the entire West into a panic.

The Comanche led to the formation of the Texas Rangers - a small force whose size and exploits may have been exaggerated, but which nonetheless was the first truly effective Indian-fighting force in the West. They learned to hunt, track, and fight Indian style, and when supplied with what was at first an obscure new invention that no one else wanted - the Colt 6-shooter - they suddenly had weapons that could truly let them fight the Comanche on their terms.

The history of Indian fighting is interesting wherever you stand on the Cowboys & Indians division, because it's a true military history. The Comanche weren't just war-whooping savages attacking like orcs, they used strategy and tactics and intelligence (they knew when Army units were diverted elsewhere, such as for the Civil War), and they picked their battles. Though they also made frequent mistakes, usually more diplomatic than military. For example, they considered taking white women captive, raping and torturing them, and then ransoming them back to be just normal business practice, and probably never really understood just how implacably this set white men against them.

I did have a bit of a problem with the titular premise of the book - that the Comanche ruled an "empire," akin perhaps to the Mayans or the Aztecs. In fact, as Gwynne points out, the Comanche were divided into five or six large "bands" who considered themselves all one people, but were led by different chiefs, none of whom had authority over the others, and there was no grand council coordinating all Comanche (at least not until the Quanah Parker era, and then only nominally). This was a mistake whites frequently made - they would negotiate a peace treaty with one particular band of Comanches, and think they had signed a treaty with the entire Comanche tribe, when in fact all the other Comanche neither knew nor cared about any agreements with some other band.

And the Comanche were also unlike the Navajo or most of the other well-known large tribes; according to Gwynne, they had little in the way of art, culture, history, or formal tribal structure. They really were quite "primitive," even compared to other Indians. So to speak of a Comanche "empire" seems to be a bit of an exaggeration - what the Comanche actually had was a very large territory over which they hunted and raided and were the acknowledged lords of the plains, until the white man came along.

The latter part of the book is mostly about Quanah Parker. Quanah, the half-white, half-Comanche son of Cynthia Ann Parker (from whom he was separated at age 12, never to see her again), was a truly remarkable individual. Described as a giant among Comanche and unusually strong and intelligent, he suffered some prejudice for his white blood but proved himself over and over again to be a better Comanche than any of his detractors. (The Comanche also were not particularly racial purists - it had long been their practice to capture children from other tribes, and the Mexicans, and then the whites, to raise as their own, supposedly in part because Comanche women, spending long, hard years on horseback themselves, had a very low fertility rate.) He become a notorious war leader, and hated his mother's people, the Texans, in particular.

This is another one of those great contradictions we are confronted with. Quanah Parker, later in life, became feted and celebrated as a "civilized" Indian. He adapted to his life as a homeowner and a celebrity and a politician, was fascinated by new technology, owning a telephone and an automobile. He was friends with Teddy Roosevelt.

But this same man had once ridden the plains and raided white settlements. There is no documented evidence that Quanah personally raped and tortured anyone, but he was known to harbor a vicious hatred for white settlers, he led Comanche war parties, and this was what Comanche war parties did. So, you can draw your own conclusions. Quanah sensibly refused to go into those sorts of details later in life.

In summary, this was a fascinating, somewhat flawed book. It told me a lot of things about the Comanche, some of which I realize I need to treat with some skepticism until I read some other primary sources. It has at least inspired me to go looking for other books on the same subject from which I might get other perspectives.

I've read good reviews of this book, so perhaps it should be next on my reading list.

And now I need to break open this solitaire game from GMT which has been sitting on my shelf for months now.

My complete list of book reviews.