POTUS #21: A crooked machine politician does a heel-face turn.

Grand Central Publishing, 2017, 336 pages

Among the Gilded Age presidents, Chester Arthur is probably one of the most forgettable. If you know him at all, it's because he's the guy who became President after James Garfield was assassinated. A vice president who never previously served in elected office and was a pure machine politician, he emerged from the corrupt, crony politics of New York City and somehow became a reformer.

Or maybe you remember when POTUSes looked like Treebeard.

Chester Arthur was born in Vermont. His parents were Irish immigrants, and apparently he was the first president to be accused of not being a natural-born US citizen: rumors circulated during the presidential campaign of 1880 that he was actually born in Ireland or Canada. While he grew up with a strict, religious, abolitionist father who was occasionally driven out of his parishes for his anti-slavery preaching, Chester turned away from his religious upbringing and became a more worldly young man, much to the distress of his parents.

His early career was meritorious. He got started as a lawyer in New York City, and in one of his most important cases, he represented a black woman who'd been forcibly removed from a streetcar by a racist conductor. He won the case, which led to the desegregation of New York City streetcars (at least on paper). Oddly, despite Arthur himself being an abolitionist and later a defender of African-American civil rights, he never really talked about this case at all.

Arthur was engaged to Ellen Herndon, the daughter of a naval officer who famously went down with his ship, the Central America, in one of the greatest naval disasters in US history. Greenberger goes into some detail on the Central America disaster, and his little side tangents into secondary characters in Arthur's life are one of the things I enjoyed about this book. (However, see below when it seems to the detriment of the historical narrative.) Ellen (or "Nell") was an ambitious social climber who had certain expectations regarding their lifestyle, which Arthur sought to fulfill. Ultimately he would provide the wealth and status she craved, but alas, she would die suddenly in 1880, just before her husband would reach the height of his career.

One of his first ventures, while he was still engaged, was to travel with a partner to Kansas in the hopes of making a fortune in this newly opened territory. But "Bleeding Kansas" was far too violent for his liking, and honestly, he was a city slicker lawyer who had no business being on the frontier. He soon returned to New York City.

When the Civil War broke out, Arthur was commissioned as a brigadier general in the New York state militia. He had no military experience and this was purely a patronage appointment, but he did a great job of fundraising and mustering troops, and reportedly was scrupulously honest, compared to most of his profiteering peers. The war, however, was awkward for him because his wife and her family were Confederate sympathizers.

After the war, Arthur rose higher in the Republican political machine. This was the era of Tammany Hall, and this is when, surrounded by wealth and cronyism, Arthur apparently began to succumb to temptation, partly encouraged by his ambitious wife (who probably retained plausible deniability about just how they were becoming so rich, but certainly enjoyed being rich).

The last several presidential biographies I've read have talked a lot about machine politics and political patronage. It is interesting reading the justifications of men like William Tweed, Chester Arthur, and Roscoe Conkling, defending what today would be considered rank corruption. They considered a political machine to be a force for effective politics; handing out government jobs and demanding "contributions" was how you kept the machine running. They acknowledged this made for a less efficient civil service, and that there was some cost to the taxpayer, but that was just a price they were willing to let the taxpayer pay.

Roscoe Conkling (who also figured largely in Hayes and Garfield's presidencies) was a handsome, arrogant New York Senator, known for being a womanizer, a "bad boy" who once threatened to kill a newspaper editor if he ran a critical expose on him, and a debonaire "rooster" who played up his fashionable appearance and stylish curled hair. He would be a lifelong enemy of Maine Senator James G. Blaine because Blaine once called him a turkey on the Senate floor, and Blaine is another figure who recurs throughout this era in several presidential biographies.

Roscoe Conkling was the heir of Boss Tweed and became the head of the New York Republican political machine, and Chester Arthur became Conkling's man. Conkling was given patronage power in New York by President Ulysses S. Grant (an honest man in a corrupt administration who also considered patronage to be just how things were done), and under Conkling, Arthur became the Collector of the Port of New York. While this required Senate confirmation, Conkling's support was enough, and Arthur now had power over a thousand jobs and the ability to collect a share of all fines and seizures in the Port of New York. Greenberger goes into detail on the operations of the New York Customs House; suffice to say it was corrupt as hell and Arthur got fat and rich.

Conkling and Arthur experienced a setback when Rutherford Hayes became President. Hayes was a reformer who swore to reform the civil service, and while he was only partially successful, he did fire Arthur from the Customs House. Ironically, this is what indirectly led to Arthur becoming president.

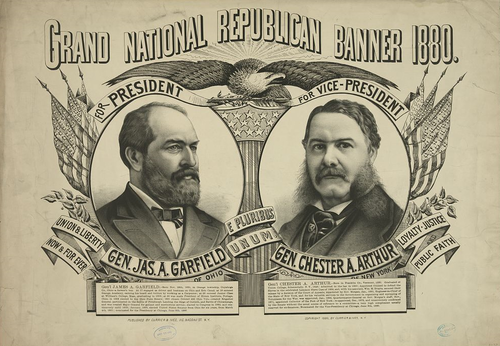

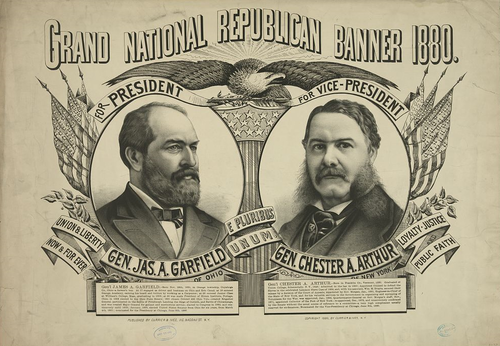

For the election of 1880, Hayes had already promised not to run for reelection, so the Republican convention was contested between former President Grant and his "Stalwarts" (including Conkling and Arthur), Conkling's old enemy Senator James Blaine, and John Sherman. There were a few other minor contenders, but mainly it was a contest between Grant (pro-patronage) and Blaine (pro-reform). After multiple ballots, neither side had enough votes to win the nomination, and Blaine and Sherman, realizing neither of them could beat Grant on their own, switched their support to dark horse James Garfield, who became the surprise nominee of the convention. Garfield was also a reformer, but more practical than Blaine, so he sought to appease the Stalwarts by choosing one of them as his running mate.

This almost caused a split between Arthur and Conkling. Conkling was furious about his loss at the Republican convention and considered Garfield his enemy. When Arthur came to tell him that he'd been offered a slot on the ticket, Conkling all but ordered him to turn it down.

Arthur looked Conkling in the eye and said "This is a greater honor than I ever imagined for myself." Perhaps he was thinking of his beloved Nell, who had died not long before and wasn't here to see this. He refused the demand of his old friend and patron, and accepted the nomination.

He and Garfield won the election against Democrat Winfield Scott Hancock, and suddenly Chester Arthur was Vice President.

Usually the vice president is not a very important person. Garfield barely spoke to him, and assigned him no important duties, and Arthur expected he'd probably spend the rest of the term not doing much of anything. But four months into his term, President Garfield was shot by a deranged office-seeker, and died a lingering, agonizing death 11 weeks later.

Suddenly everyone was shitting bricks that grifting, corrupt Chester fucking Arthur, a lackey of Roscoe Conkling and the Tweed machine, was President of the United States. Political cartoons of the time made the public's perception clear:

No one was shitting bricks more than Arthur himself. He was not prepared to become president. It seems he knew, deep down, that he was not a good enough man and had no business being in the White House. Which led to one of the most notable heel-face turns in presidential history.

Roscoe Conkling, of course, who had long since made up with Arthur (even though Arthur made his hated nemesis James Blaine Secretary of State), thought he was now practically co-president. He strode into the White House with the expectation that his old friend and loyal lieutenant Chester would award him all the patronage appointments he demanded. To his surprise and outrage, Arthur said no, and would then go on to become a reformer. He would even sign the Pendleton Act, which was the first major civil service reform act, requiring that all federal positions be chosen by merit, and prohibiting the collection of mandatory "donations" from federal employees by political parties. The latter provision was only loosely enforced—political machines don't fall apart that quickly—but it was the beginning of a professionalized federal workforce.

Besides civil service reform, Arthur made sincere if tepid efforts to improve relations with Native Americans and defend black civil rights. He vetoed the first Chinese Exclusion Act, but signed a subsequent, only slightly modified one. Historians generally consider Chester Arthur to have been a mid president; he was competent enough but accomplished nothing really exceptional during his term. He vetoed the notorious Rivers and Harbors Act, which was essentially a massive handout of pork barrel projects. Congress overrode his veto, which probably cost the Republicans the House in 1882 and the White House in 1884. Arthur also began modernizing the US Navy, which was in sad shape in the years following the Civil War.

In 1884, he made a half-hearted bid for reelection, but even his supporters realized he wasn't serious about it. They did not realize that the reason was that he was dying, of what is now known as nephritis. According to Greenberger, he had been sick throughout the last half of his presidency and only sought the Republican nomination to avoid showing weakness, and probably didn't really want it.

He was not selected; the Republican nominee was James Blaine, who would lose to Democrat Grover Cleveland.

I've read books in this series before. They are like sawdust.

This was a very good and concise biography that made one of the forgotten presidents interesting. Greenberger tells many interesting stories about Garfield and other political figures, seems to have a fair amount of insight into the rather unknown Arthur's personality, and doesn't glaze his subject too much. However, I have to fault it for two reasons.

First, there is a Goodreads review that makes a convincing case that Greenberger cribbed entire passages from an older, thicker Arthur biography, Gentleman Boss: The Life of Chester Arthur, by Thomas C. Reeves. While every biographer draws heavily on earlier sources, word-for-word cribbing is almost unforgivable.

Second, there is Greenberger's treatment of Julia Sand.

Julia Sand was an unmarried woman from a well-to-do family living in New York City. In 1881, while Garfield was still dying, the invalid Julia began writing to Chester Arthur. Her first letter was, well:

Basically, "You're a loser, and everyone expects you to suck. Do better!" What possessed her to start writing to the then-Vice President? How did Arthur feel, upon reading this?

She continued to write to him after he became President, and her letters were full of encouragement, moral remonstration, and occasional flirtatiousness. She had an unusual interest in politics and opinions about everything Arthur did, and would sometimes praise him for listening to his better nature, and sometimes scold him for disappointing her (such as when he failed to veto the second Chinese Exclusion Act). It's not hard to form a picture of a reclusive young woman who somehow developed something of a crush on the President and began to see herself as an angel on his shoulder.

Greenberger inserts excerpts from Julia Sand's letters into the last third of the book, as a sort of running commentary on Arthur's presidency, and heavily implies that Arthur was affected, if not guided, by her counsel and the constant encouragement of this strange woman. Greenberger even calls her "the conscience of the President." The implication is that Chester Arthur's return to virtue and becoming a reformer president was due to Julia Sand.

We know that Arthur read her letters, because after his death, an envelope with 23 of them was found among his effects. And he even visited her once, in her family home in New York City! The visit apparently was brief, poor Julia was shy and tongue-tied, and despite her asking him in her letters to come again, he never did.

The fact is, though, we don't actually know what Arthur really thought of her and her letters. Maybe he was amused by his little fangirl. Maybe he visited her the one time because he was curious to meet this weird lady who had so much unsolicited advice for him. Greenberger's narrative is not implausible, but it seems constructed to make a good story and not something based on solid evidence.

Arthur was ashamed of his past as a political crony, and ordered almost all of his correspondence to be burned after his death, which left biographers like Greenberger with not much to work with and a lot of space to fill in the blanks. Julia Sand outlived Arthur by 50 years, apparently remained a reclusive "maiden aunt" who occasionally wrote magazine articles, and we only know about her now because one of Arthur's grandsons became curious about this one-sided correspondence and went looking for her relatives.

I enjoyed this biography, and like most C-list presidents, I really liked finding out about the politics of the time and how even someone as historically inconsequential as Chester Arthur had a place in American history, and has some things to tell us about politics today. (Accused of being a fake US citizen, long before Obama! A president who actually changed his ways and did the right thing! A president who valued a professional civil service not beholden to party loyalties.)

Chester Arthur's story is also the story of the Gilded Age, and how the growing power of corporations and the 1% shaped politics as America became richer and also experienced growing wealth inequality. The sequence of post-war presidents from Grant to Hayes to Garfield and Arthur tells an ongoing story of recurring character and political factions, and the issues that determined elections in the wake of the Civil War and Reconstruction. Reading the latter presidents' biographies gives a lot more context when you come to 21 and recognize names like Conkling and Blaine, who are known only to historians today but were the Pelosis and Schumers of their day.

Is this the best biography of Chester Arthur? Well, I chose it because it was relatively recent and relatively short, as opposed to the much longer book by Reeves, which reviews suggest is much more thorough and also much more tedious. I think Greenberger did a good job of making Arthur a readable personality, but it seems he got a little lazy with his cribbing, and also really had a story he wanted to tell about Julia Sand. (Maybe he was hoping for a Netflix series?) This is a good book for someone like me progressing through presidents in order, but it's probably not the best source if you really want to dig into the era.

My complete list of book reviews.

Grand Central Publishing, 2017, 336 pages

Despite his promising start as a young man, by his early 50s Chester A. Arthur was known as the crooked crony of New York machine boss Roscoe Conkling. For years Arthur had been perceived as unfit to govern, not only by critics and the vast majority of his fellow citizens but by his own conscience. As President James A. Garfield struggled for his life, Arthur knew better than his detractors that he failed to meet the high standard a president must uphold.

And yet, from the moment President Arthur took office, he proved to be not just honest but brave, going up against the very forces that had controlled him for decades. He surprised everyone - and gained many enemies - when he swept house and took on corruption, civil rights for Blacks, and issues of land for Native Americans.

A mysterious young woman deserves much of the credit for Arthur's remarkable transformation. Julia Sand, a bedridden New Yorker, wrote Arthur nearly two dozen letters urging him to put country over party, to find "the spark of true nobility" that lay within him. At a time when women were barred from political life, Sand's letters inspired Arthur to transcend his checkered past - and changed the course of American history.

Among the Gilded Age presidents, Chester Arthur is probably one of the most forgettable. If you know him at all, it's because he's the guy who became President after James Garfield was assassinated. A vice president who never previously served in elected office and was a pure machine politician, he emerged from the corrupt, crony politics of New York City and somehow became a reformer.

Or maybe you remember when POTUSes looked like Treebeard.

Chester Arthur was born in Vermont. His parents were Irish immigrants, and apparently he was the first president to be accused of not being a natural-born US citizen: rumors circulated during the presidential campaign of 1880 that he was actually born in Ireland or Canada. While he grew up with a strict, religious, abolitionist father who was occasionally driven out of his parishes for his anti-slavery preaching, Chester turned away from his religious upbringing and became a more worldly young man, much to the distress of his parents.

His early career was meritorious. He got started as a lawyer in New York City, and in one of his most important cases, he represented a black woman who'd been forcibly removed from a streetcar by a racist conductor. He won the case, which led to the desegregation of New York City streetcars (at least on paper). Oddly, despite Arthur himself being an abolitionist and later a defender of African-American civil rights, he never really talked about this case at all.

Arthur was engaged to Ellen Herndon, the daughter of a naval officer who famously went down with his ship, the Central America, in one of the greatest naval disasters in US history. Greenberger goes into some detail on the Central America disaster, and his little side tangents into secondary characters in Arthur's life are one of the things I enjoyed about this book. (However, see below when it seems to the detriment of the historical narrative.) Ellen (or "Nell") was an ambitious social climber who had certain expectations regarding their lifestyle, which Arthur sought to fulfill. Ultimately he would provide the wealth and status she craved, but alas, she would die suddenly in 1880, just before her husband would reach the height of his career.

One of his first ventures, while he was still engaged, was to travel with a partner to Kansas in the hopes of making a fortune in this newly opened territory. But "Bleeding Kansas" was far too violent for his liking, and honestly, he was a city slicker lawyer who had no business being on the frontier. He soon returned to New York City.

When the Civil War broke out, Arthur was commissioned as a brigadier general in the New York state militia. He had no military experience and this was purely a patronage appointment, but he did a great job of fundraising and mustering troops, and reportedly was scrupulously honest, compared to most of his profiteering peers. The war, however, was awkward for him because his wife and her family were Confederate sympathizers.

After the war, Arthur rose higher in the Republican political machine. This was the era of Tammany Hall, and this is when, surrounded by wealth and cronyism, Arthur apparently began to succumb to temptation, partly encouraged by his ambitious wife (who probably retained plausible deniability about just how they were becoming so rich, but certainly enjoyed being rich).

The last several presidential biographies I've read have talked a lot about machine politics and political patronage. It is interesting reading the justifications of men like William Tweed, Chester Arthur, and Roscoe Conkling, defending what today would be considered rank corruption. They considered a political machine to be a force for effective politics; handing out government jobs and demanding "contributions" was how you kept the machine running. They acknowledged this made for a less efficient civil service, and that there was some cost to the taxpayer, but that was just a price they were willing to let the taxpayer pay.

Roscoe Conkling (who also figured largely in Hayes and Garfield's presidencies) was a handsome, arrogant New York Senator, known for being a womanizer, a "bad boy" who once threatened to kill a newspaper editor if he ran a critical expose on him, and a debonaire "rooster" who played up his fashionable appearance and stylish curled hair. He would be a lifelong enemy of Maine Senator James G. Blaine because Blaine once called him a turkey on the Senate floor, and Blaine is another figure who recurs throughout this era in several presidential biographies.

Roscoe Conkling was the heir of Boss Tweed and became the head of the New York Republican political machine, and Chester Arthur became Conkling's man. Conkling was given patronage power in New York by President Ulysses S. Grant (an honest man in a corrupt administration who also considered patronage to be just how things were done), and under Conkling, Arthur became the Collector of the Port of New York. While this required Senate confirmation, Conkling's support was enough, and Arthur now had power over a thousand jobs and the ability to collect a share of all fines and seizures in the Port of New York. Greenberger goes into detail on the operations of the New York Customs House; suffice to say it was corrupt as hell and Arthur got fat and rich.

Conkling and Arthur experienced a setback when Rutherford Hayes became President. Hayes was a reformer who swore to reform the civil service, and while he was only partially successful, he did fire Arthur from the Customs House. Ironically, this is what indirectly led to Arthur becoming president.

For the election of 1880, Hayes had already promised not to run for reelection, so the Republican convention was contested between former President Grant and his "Stalwarts" (including Conkling and Arthur), Conkling's old enemy Senator James Blaine, and John Sherman. There were a few other minor contenders, but mainly it was a contest between Grant (pro-patronage) and Blaine (pro-reform). After multiple ballots, neither side had enough votes to win the nomination, and Blaine and Sherman, realizing neither of them could beat Grant on their own, switched their support to dark horse James Garfield, who became the surprise nominee of the convention. Garfield was also a reformer, but more practical than Blaine, so he sought to appease the Stalwarts by choosing one of them as his running mate.

This almost caused a split between Arthur and Conkling. Conkling was furious about his loss at the Republican convention and considered Garfield his enemy. When Arthur came to tell him that he'd been offered a slot on the ticket, Conkling all but ordered him to turn it down.

Arthur looked Conkling in the eye and said "This is a greater honor than I ever imagined for myself." Perhaps he was thinking of his beloved Nell, who had died not long before and wasn't here to see this. He refused the demand of his old friend and patron, and accepted the nomination.

He and Garfield won the election against Democrat Winfield Scott Hancock, and suddenly Chester Arthur was Vice President.

Usually the vice president is not a very important person. Garfield barely spoke to him, and assigned him no important duties, and Arthur expected he'd probably spend the rest of the term not doing much of anything. But four months into his term, President Garfield was shot by a deranged office-seeker, and died a lingering, agonizing death 11 weeks later.

Suddenly everyone was shitting bricks that grifting, corrupt Chester fucking Arthur, a lackey of Roscoe Conkling and the Tweed machine, was President of the United States. Political cartoons of the time made the public's perception clear:

No one was shitting bricks more than Arthur himself. He was not prepared to become president. It seems he knew, deep down, that he was not a good enough man and had no business being in the White House. Which led to one of the most notable heel-face turns in presidential history.

Roscoe Conkling, of course, who had long since made up with Arthur (even though Arthur made his hated nemesis James Blaine Secretary of State), thought he was now practically co-president. He strode into the White House with the expectation that his old friend and loyal lieutenant Chester would award him all the patronage appointments he demanded. To his surprise and outrage, Arthur said no, and would then go on to become a reformer. He would even sign the Pendleton Act, which was the first major civil service reform act, requiring that all federal positions be chosen by merit, and prohibiting the collection of mandatory "donations" from federal employees by political parties. The latter provision was only loosely enforced—political machines don't fall apart that quickly—but it was the beginning of a professionalized federal workforce.

Besides civil service reform, Arthur made sincere if tepid efforts to improve relations with Native Americans and defend black civil rights. He vetoed the first Chinese Exclusion Act, but signed a subsequent, only slightly modified one. Historians generally consider Chester Arthur to have been a mid president; he was competent enough but accomplished nothing really exceptional during his term. He vetoed the notorious Rivers and Harbors Act, which was essentially a massive handout of pork barrel projects. Congress overrode his veto, which probably cost the Republicans the House in 1882 and the White House in 1884. Arthur also began modernizing the US Navy, which was in sad shape in the years following the Civil War.

In 1884, he made a half-hearted bid for reelection, but even his supporters realized he wasn't serious about it. They did not realize that the reason was that he was dying, of what is now known as nephritis. According to Greenberger, he had been sick throughout the last half of his presidency and only sought the Republican nomination to avoid showing weakness, and probably didn't really want it.

He was not selected; the Republican nominee was James Blaine, who would lose to Democrat Grover Cleveland.

I've read books in this series before. They are like sawdust.

This was a very good and concise biography that made one of the forgotten presidents interesting. Greenberger tells many interesting stories about Garfield and other political figures, seems to have a fair amount of insight into the rather unknown Arthur's personality, and doesn't glaze his subject too much. However, I have to fault it for two reasons.

First, there is a Goodreads review that makes a convincing case that Greenberger cribbed entire passages from an older, thicker Arthur biography, Gentleman Boss: The Life of Chester Arthur, by Thomas C. Reeves. While every biographer draws heavily on earlier sources, word-for-word cribbing is almost unforgivable.

Second, there is Greenberger's treatment of Julia Sand.

Julia Sand was an unmarried woman from a well-to-do family living in New York City. In 1881, while Garfield was still dying, the invalid Julia began writing to Chester Arthur. Her first letter was, well:

The hours of Garfield's life are numbered – before this meets your eye, you may be President. The people are bowed in grief; but – do you realize it? – not so much because he is dying, as because you are his successor. What president ever entered office under circumstances so sad?...

The day [Garfield] was shot, the thought rose in a thousand minds that you might be the instigator of the foul act. Is not that a humiliation which cuts deeper than any bullet can pierce?

Your kindest opponents say 'Arthur will try to do right' – adding gloomily – 'He won't succeed though making a man President cannot change him.'...But making a man President can change him! Great emergencies awaken generous traits which have lain dormant half a life. If there is a spark of true nobility in you, now is the occasion to let it shine. Faith in your better nature forces me to write to you – but not to beg you to resign. Do what is more difficult & brave. Reform! It is not proof of highest goodness never to have done wrong, but it is proof of it, sometimes in ones career, to pause & ponder, to recognize the evil, to turn resolutely against it.... Once in awhile [sic?] there comes a crisis which renders miracles feasible. The great tidal wave of sorrow which has rolled over the country has swept you loose from your old moorings & set you on a mountaintop, alone.

Disappoint our fears. Force the nation to have faith in you. Show from the first that you have none but the purest of aims.

You cannot slink back into obscurity, if you would. A hundred years hence, school boys will recite your name in the list of presidents & tell of your administration. And what shall posterity say? It is for you to choose....

— Julia Sand

Basically, "You're a loser, and everyone expects you to suck. Do better!" What possessed her to start writing to the then-Vice President? How did Arthur feel, upon reading this?

She continued to write to him after he became President, and her letters were full of encouragement, moral remonstration, and occasional flirtatiousness. She had an unusual interest in politics and opinions about everything Arthur did, and would sometimes praise him for listening to his better nature, and sometimes scold him for disappointing her (such as when he failed to veto the second Chinese Exclusion Act). It's not hard to form a picture of a reclusive young woman who somehow developed something of a crush on the President and began to see herself as an angel on his shoulder.

Greenberger inserts excerpts from Julia Sand's letters into the last third of the book, as a sort of running commentary on Arthur's presidency, and heavily implies that Arthur was affected, if not guided, by her counsel and the constant encouragement of this strange woman. Greenberger even calls her "the conscience of the President." The implication is that Chester Arthur's return to virtue and becoming a reformer president was due to Julia Sand.

We know that Arthur read her letters, because after his death, an envelope with 23 of them was found among his effects. And he even visited her once, in her family home in New York City! The visit apparently was brief, poor Julia was shy and tongue-tied, and despite her asking him in her letters to come again, he never did.

The fact is, though, we don't actually know what Arthur really thought of her and her letters. Maybe he was amused by his little fangirl. Maybe he visited her the one time because he was curious to meet this weird lady who had so much unsolicited advice for him. Greenberger's narrative is not implausible, but it seems constructed to make a good story and not something based on solid evidence.

Arthur was ashamed of his past as a political crony, and ordered almost all of his correspondence to be burned after his death, which left biographers like Greenberger with not much to work with and a lot of space to fill in the blanks. Julia Sand outlived Arthur by 50 years, apparently remained a reclusive "maiden aunt" who occasionally wrote magazine articles, and we only know about her now because one of Arthur's grandsons became curious about this one-sided correspondence and went looking for her relatives.

I enjoyed this biography, and like most C-list presidents, I really liked finding out about the politics of the time and how even someone as historically inconsequential as Chester Arthur had a place in American history, and has some things to tell us about politics today. (Accused of being a fake US citizen, long before Obama! A president who actually changed his ways and did the right thing! A president who valued a professional civil service not beholden to party loyalties.)

Chester Arthur's story is also the story of the Gilded Age, and how the growing power of corporations and the 1% shaped politics as America became richer and also experienced growing wealth inequality. The sequence of post-war presidents from Grant to Hayes to Garfield and Arthur tells an ongoing story of recurring character and political factions, and the issues that determined elections in the wake of the Civil War and Reconstruction. Reading the latter presidents' biographies gives a lot more context when you come to 21 and recognize names like Conkling and Blaine, who are known only to historians today but were the Pelosis and Schumers of their day.

Is this the best biography of Chester Arthur? Well, I chose it because it was relatively recent and relatively short, as opposed to the much longer book by Reeves, which reviews suggest is much more thorough and also much more tedious. I think Greenberger did a good job of making Arthur a readable personality, but it seems he got a little lazy with his cribbing, and also really had a story he wanted to tell about Julia Sand. (Maybe he was hoping for a Netflix series?) This is a good book for someone like me progressing through presidents in order, but it's probably not the best source if you really want to dig into the era.

My complete list of book reviews.