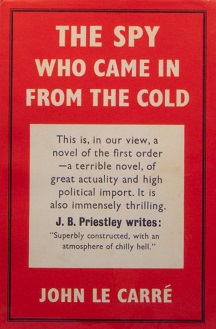

Published by Victor Gollancz Ltd., 1963, 256 pages

The story of Alec Leamas - a 50-year-old professional secret agent who has grown stale in espionage, who longs to "come in from the cold" - and how he undertakes one last assignment before that hoped-for retirement.

Leamas is responsible for keeping the double agents under his care undercover and alive, but East Germans start killing them, so he gets called back to London by Control, his spy master. Yet instead of giving Leamas the boot, Control gives him a scary assignment: play the part of a disgraced agent, a sodden failure everybody whispers about.

So I just read From Russia With Love and waxed enthusiastic about the guilty pleasures of Bond novels, and then for contrast, read John le Carré's classic. The Spy Who Came in from the Cold is actually the third spy novel le Carré wrote, and has several recurring characters, but it was his break-out bestseller and is frequently put on "top 100" books lists.

This is a Cold War spy story written in the same time period as most of Fleming's novels. Like Bond, Alec Leamas is a secret agent working for British intelligence. The similarity ends there. Fleming's novels were romantic adventures that glamorized the spy game. Bond might occasionally feel moral qualms, but he never questions his missions, and there's never a doubt that MI6 are the good guys fighting the despicable, evil commies. The Spy Who Came in From the Cold is gray all the way through, and no one is a hero.

Alec Leamas is in charge of British operations in Berlin. One by one, all of his spies in East Germany have been picked off in the last few years; when his last man in East Berlin is shot trying to get out, he is called back to London. He's 50, close to retirement, drinks too much, and expects to be put on desk duty or just pensioned out after this string of failures. Instead, Control (the "M" of le Carré's novels) asks him to go on one more mission before he can "come in from the cold." Their target is Hans-Dieter Mundt, the head of East Germany's Secret Service and the man who is responsible for taking apart Leamas's spy network. Their plan is to frame Mundt as a British double-agent and thus get the East Germans to execute him.

Leamas "retires" from British intelligence. He is given a paltry pension, amidst rumors that he was found guilty of theft. He drifts in and out of jobs. He becomes an alcoholic. He's a drunken, bitter burn-out, and his life hits a nadir when he assaults a grocer and is sent to prison for six months.

Everything goes according to plan. The next chapter after he gets out is called "Contact."

What follows is a complex, sophisticated story that feels much more like how real intelligence networks operate than any of Fleming's adventures with psychopathic assassins and gadget-wielding secret agents. It's all seedy, furtive meetings followed by elaborate interviews, with everyone assuming (usually correctly) that everyone else is always lying. Everyone has complex motivations -- they aren't just acting out of nationalism, greed, or megalomania. Leamas is "acting" the part of an embittered alcoholic who's ready to turn on his former masters, but he's convincing because it's just barely an act. He is compromised by his association with Liz Gold, a young Jewish communist he meets by chance while in one of his post-intelligence jobs, and who is dragged into the scheme despite his best efforts to keep her out of it. When he meets his East German contacts, the story becomes even more complicated. He ends up going behind the Iron Curtain. He is interrogated by a Jewish East German spy named Fiedler. Leamas comes to like and respect Fiedler, who serves the East Germans out of sincere ideological convictions, as opposed to Mundt, who's a former Nazi who serves communists as readily as fascists and remains a vicious anti-Semite.

To describe any more would be to ruin the story, as it contains one twist after another. The double-crosses and betrayals are cold, calculating, and completely believable, and the story remains tense and unpredictable all the way to the ending.

A Rebuttal to Bond

"What the hell do you think spies are? Moral philosophers measuring everything they do against the word of God or Karl Marx? They're not. They're just a bunch of seedy, squalid bastards like me. Little men -- drunkards, queers, henpecked husbands, civil servants playing cowboys and Indians to brighten their rotten little lives. Do you think they sit like monks in cells balancing right against wrong?"

Le Carré is totally subverting the romanticism of James Bond. Where Fleming told stories of good guys vs. bad guys, Le Carré shows that both sides embrace "the ends justify the means" and will take any traitors they can get, and that innocent people get hurt no matter what. There is action, there are narrow escapes, and there is gunplay, but none of it is cinematic. It's all grimy rendezvouses (in another subversion of Bond tropes, one of Leamas's meetings with his handlers is at a strip club, and it's portrayed as the seedy encounter it is) and shots in the dark, and betrayals happen on paper, not during gunfights. The climax takes place at an East German tribunal assembled to try Mundt for treason.

Le Carré's writing is short on description; the people and scenery hardly matter in terms of their appearance. This is a deeply psychological and only slightly political novel, but very little is spelled out. Even during the "reveals," the infodumps are sparse and require the reader to pay close attention to decode everything that really happened. It's an intense literary thriller that captures the harsh reality and moral ambiguity of the Cold War perfectly.

The movie is black and white, but the story isn't

The 1965 movie adaptation stars Richard Burton as Alec Leamas. Though most films were filmed in color by then, black and white was a good choice for this movie, which follows the book almost exactly.

Like the novel, it's low-key and the tension is carried by dialog, not action. It's as much a courtroom drama as a spy thriller (with a tribunal judge who I swear is a dead-ringer for Maggie Smith as Minerva McGonagall, except Maggie Smith was only 31 when this was filmed) and does a beautiful job of extracting all the understated tension and moral complexity of the book. Even in the moments of deadly confrontation, there's no crescendo in the soundtrack, which is almost nonexistent throughout the movie, making it a pure actor's movie. While the book, as usual, is better, the film is great, but it's sufficiently complex that I really recommend reading the book first.

Verdict: A book anyone who likes spy novels should read. It's grim and gritty and realistic with sharp plot twists and compelling characters, and captures an era that's fading from memory, the world of the Cold War and the Iron Curtain.

The Spy Who Came in from the Cold is on the list of 1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die, though I did not read it specifically for the ![]() books1001 challenge. But it remains unassigned, so you could!

books1001 challenge. But it remains unassigned, so you could!